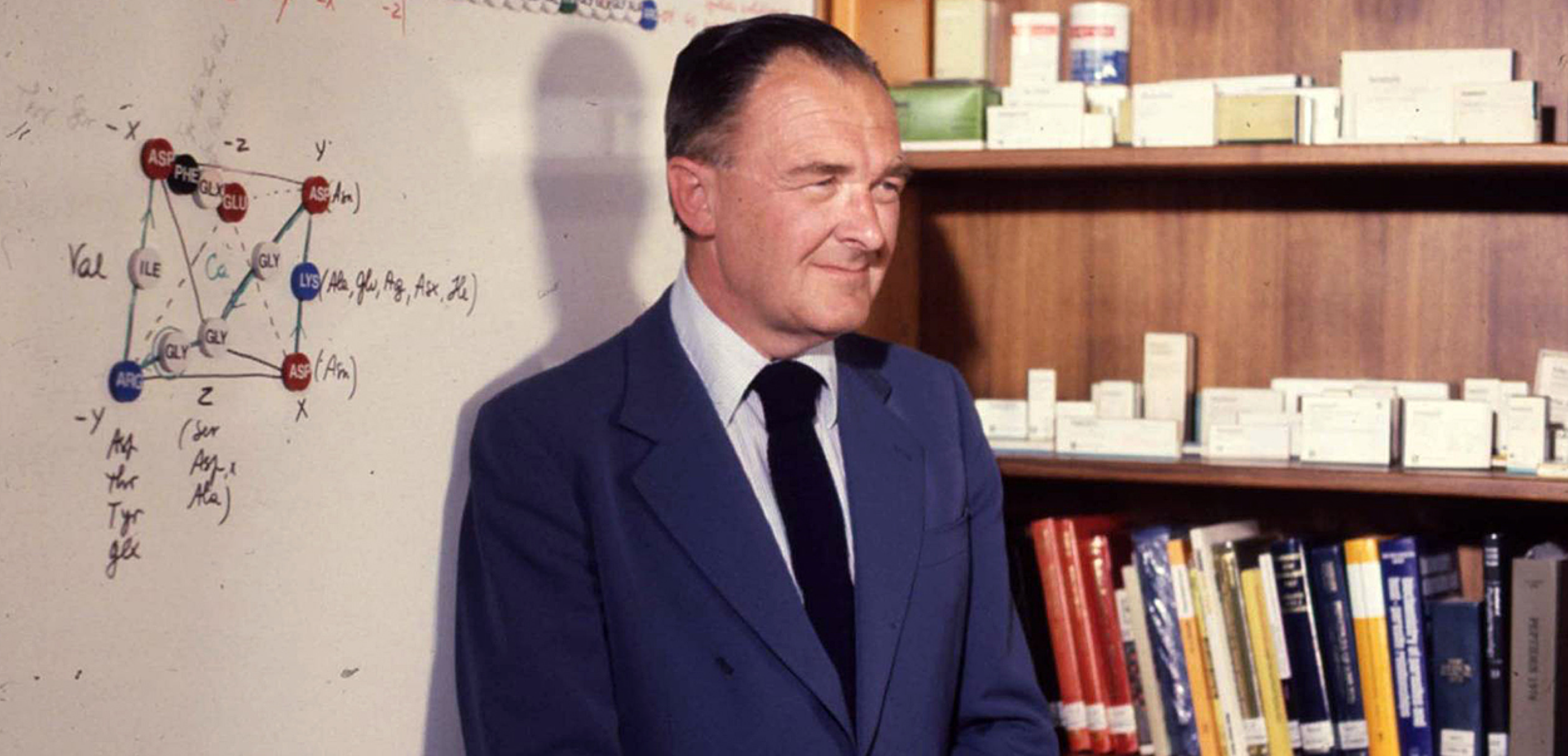

Portrait of Innovation

By John Rennie, Science Editor & Journalist

The late Paul Janssen—“Dr. Paul” to much of the world of pharmaceutical research—loved to ask, “What’s new?” For him, it was no casual opening to small talk. The world cried out for medical cures and treatments, and Janssen recognized that only a tenacious pursuit of novel molecules with therapeutic promise would yield them. The chemists in his employ knew it, too: when he regularly posed his favorite question to them, it was both a cheerful query and a firm challenge to keep turning up new observations, new ideas, and new leads.

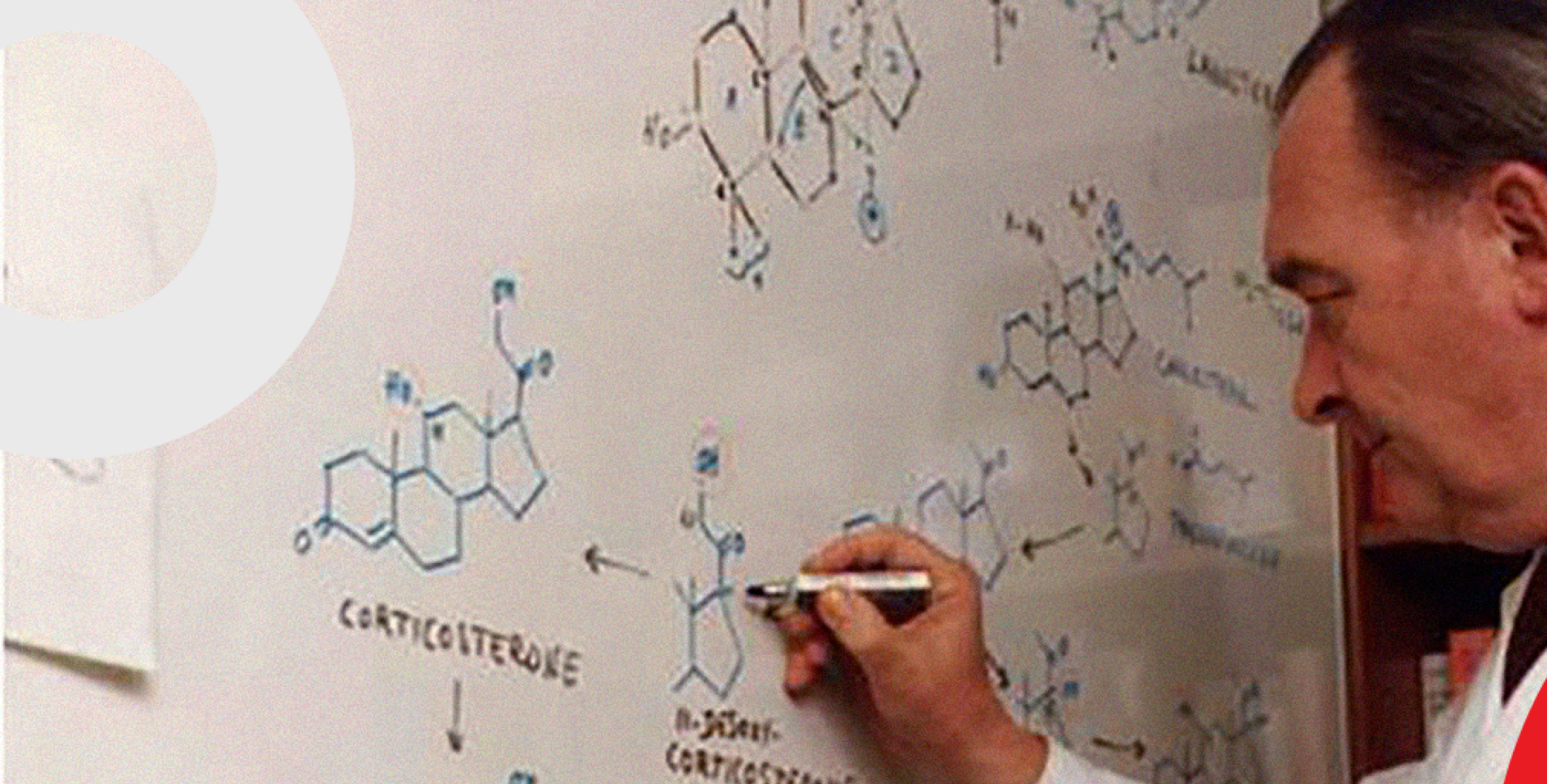

Thanks to that drive and the heights to which it pushed the company he headed, Janssen is widely considered the most prolific drug inventor of all time. He and the research teams he headed at Janssen Pharmaceutica (and the earlier versions of that company) are credited with discovering more than 80 new active compounds of interest. Some of those medications led to breakthroughs in psychiatric treatment, pain management and anesthesia, the treatment of parasitic and infectious diseases, and a host of other medical specialties. Five of those medications are on the current WHO list of essential medicines. At the time of his death in 2003, he held more than 100 patents and was a listed author on more than 850 scientific publications. He was the recipient of more than 80 medical prizes and held honorary doctorates and memberships in dozens of organizations.

“He respected courage as much as intelligence and experience,” wrote Paul J. Lewi, a longtime colleague, with Adam Smith in a 2007 article about Janssen’s approach to research for R&D Management. That courage Janssen inspired in others, they added, pushed them to “excelling beyond limits that they themselves had thought unattainable.”

When Paul Adriaan Jan Janssen was born in 1926 in Turnhout, Belgium, his father, Constant, was a successful general practitioner who dreamed of being an entrepreneur. Shortly later, Constant struck a deal to import and distribute pharmaceuticals from Gedeon Richter, a Hungarian manufacturer, into Belgium, its colony in Congo, and the Netherlands. By 1934 he was operating the company as N.V. Produkten Richter, and in 1938 he gave up his medical practice to concentrate on the flourishing trade in vitamins, organ extracts, and other traditional medications.

His father’s example undoubtedly shaped young Paul’s eventual career choice, but a tragedy inspired it more. When Paul was in high school, his four-year-old sister died of tubercular meningitis—a condition that was almost untreatable in that essentially pre-antibiotic time. Her loss made him decide to devote his life to medical research, as he often later explained.

Despite the Nazi occupation of Belgium during World War II, Janssen managed to enroll secretly at the Faculté Universitaire Notre Dame de la Paix in Namur, where he applied himself to learning chemistry, biology, and physics. He continued with medical studies at the Catholic University of Leuven in 1945. For six months in 1948 he traveled in the United States to tour current drug research facilities and to acquaint himself with then state-of-the-art procedures, then returned to Europe and the University of Ghent, from which he graduated with honors as a general medical practitioner in 1951.

Two years of obligatory military service then followed, during which Janssen still managed to work as an assistant in illustrious pharmacology laboratories at the University of Cologne and the University of Ghent.

In 1953, Janssen could have joined any number of research laboratories, but he was instead determined to start his own. A powerful idea had taken root in his thinking: that the chemical structures of compounds directly related to their physiological effects, and that by systematically modifying promising molecules one could efficiently find new, desirable synthetic drugs. The legendary Paul Ehrlich, the Nobel laureate inventor of treatments for syphilis and other diseases, had pioneered this medicinal chemistry approach decades previously but Janssen knew its promise had barely been scratched.

Returning to Turnhout, Janssen asked his father for a loan of 50,000 Belgian francs and workspace on the third floor of the family business. He and four assistants then set to work on a highly focused program of developing medically important drug compounds quickly, because Janssen recognized doing so would be a financial necessity if his new venture was to survive and remain independent.

Within a year, they had synthesized about 500 compounds; within three years, more than 1,100—an astonishing rate of productivity. The fifth compound they created, ambucetamide, proved to be highly effective as an antispasmodic for treating menstrual pain, and it became the first big winner for Janssen’s young company when it hit the market in 1955. Other important drugs born from those early compounds included isopropamide, a treatment for peptic ulcers and gastrointestinal pain, the anti-diarrheal drug diphenoxylate, and the painkiller dextromoramide, all of which propelled Janssen’s laboratory to fame.

By 1957, the success of Janssen’s company—then called the N.V. Research Laboratorium Dr. C. Janssen—led him to expand and move it to the campus of a former military base in Beerse. There, Janssen realized two of his greatest and longest-lasting pharmaceutical contributions.

The first, created in 1958, was the neuroleptic haloperidol, which helped to revolutionize the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Through the first half of the 20th century, the prospects for people suffering from schizophrenia had altered little from the era of physical restraint in Victorian madhouses. The introduction of the drug chlorprozamine in the 1950s had helped to change that, but its heavy sedative effects were unsatisfactory for many. Janssen’s haloperidol reduced the symptoms of psychosis without making patients drowsy. It eventually became the most commonly prescribed of the drugs called typical antipsychotics and is still used widely around the globe.

Anesthesia and the treatment of pain were similarly transformed by Janssen’s development of fentanyl in 1960. Fentanyl is a fast-acting, short duration opioid roughly 100 times as potent as morphine but less likely to cause nausea, which makes it almost ideal as a surgical anesthetic. Because fentanyl can also be delivered to the body in a variety of ways, including a slow-release transdermal patch, it has become the most widely prescribed analgesic drug in the world for the treatment of moderate to severe pain, particularly chronic pain from cancer. Janssen oversaw the creation of many other successful analgesics in the fentanyl family, including the anesthetic sufentanil, which is 1,000 times as potent as morphine and particularly well-suited for lengthy surgeries.

Janssen’s colleagues, friends, and rivals have frequently speculated about the secret to his extraordinary productivity. Part of it, surely, was his devotion to Ehrlich’s medicinal pharmaceutical approach and the systematic strategies he employed to explore the properties of new compounds. Pharmaceutical discovery may always depend on an element of luck, but Janssen understood how to improve the odds in his favor—and the importance of keeping his focus on genuinely therapeutic compounds, not just interesting chemistry. As Sir James Black of King’s College London wrote in a personal appreciation of Janssen in 2005, “As far as I know, Dr. Paul never started a project without a conception in his head, a conception that not only specified a chemical starting place, a ‘lead’ molecule, with appropriate bioassays but also embodied foresight of how his invention would deliver clinical utility.”

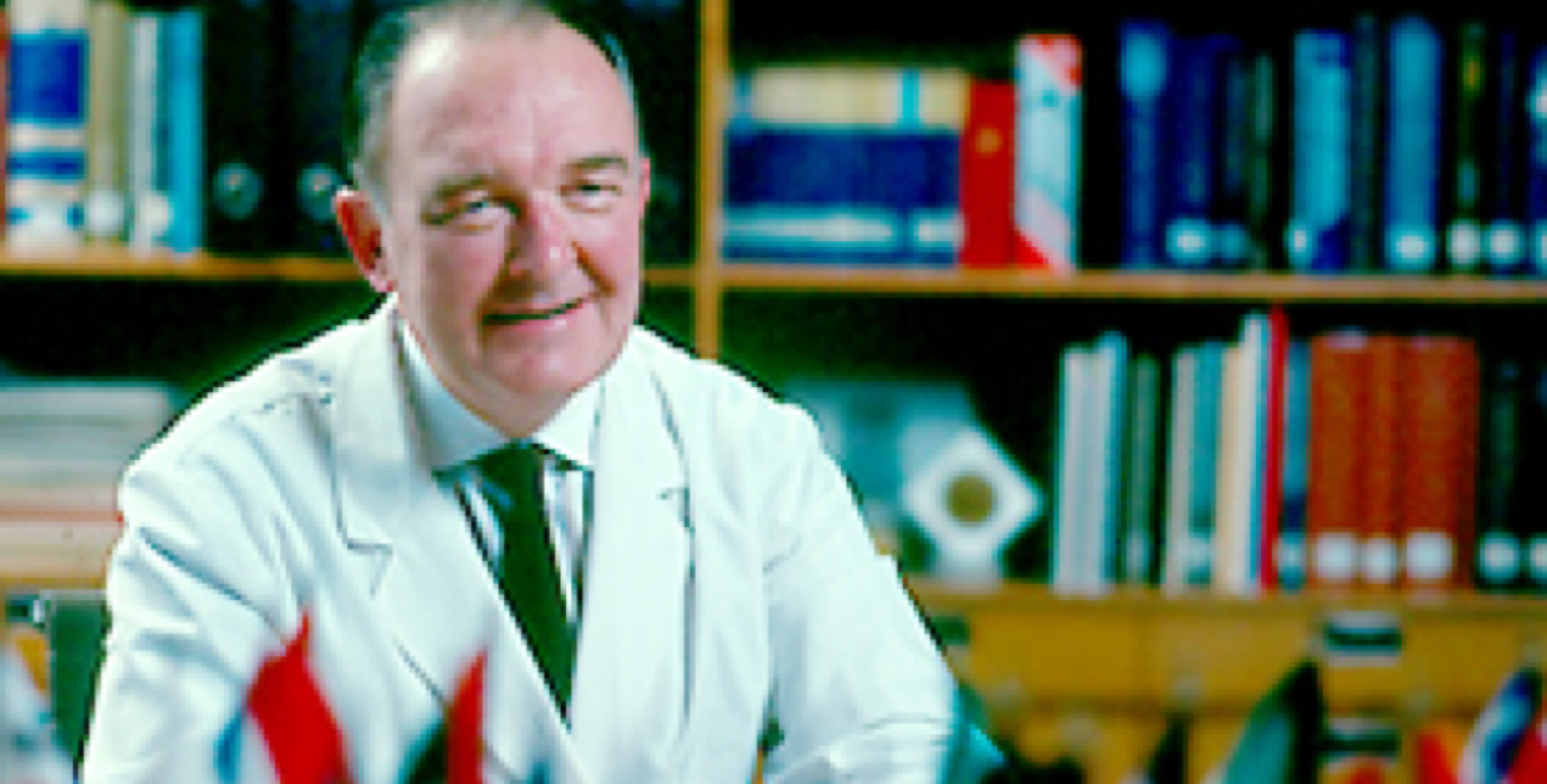

When reading, listening, and thinking about chemical concepts, Janssen frequently drew models of molecules by hand on scraps of paper; he believed that doing so helped him build a deeper understanding and intuition about the chemical structures. Sir John Black recalls, “I often watched him at meetings, when bored with the proceedings, finding solace inside his head as he doodled new chemical compounds!”

Still, Janssen was just one man, and the ascendance of Janssen Pharmaceutica came from the efforts of many researchers there. His management style was at least as important a part of his genius as his chemistry instincts were.

By all accounts, Janssen disliked ungainly hierarchies and bureaucratic inefficiency. He therefore favored a much more horizontal organizational chart for his research groups and encouraged the leaders of laboratories to operate independently and creatively. As for his own role, “I am the conductor of an orchestra,” Janssen liked to say.

A conductor, yes—but Janssen was certainly not hands-off. He checked in with all his labs for frequent briefings, and those answering his ever-present “What’s new?” knew to expect his attention and encouragement but also the weight of his firmly critical, constructive scrutiny.

Lewi and Smith noted that Janssen typically started his day with a briefing from the coordinator of research on the latest data from the labs, after which he toured from lab to lab to hear more about the most interesting results. Near the conclusion of each interview, Lewi and Smith wrote, “it was not unusual for a scientist to take a spoon or something and give a few brief taps on the tubes of the central heating system as a warning sign for those working further down the corridor: take care; be prepared; he’s coming; don’t get taken by surprise and see to it that you have ‘something new’ ready at hand.”

As Theodore Stanley, Talmage D. Egan, and Hugo Van Aken explained in a 2008 article for Anesthesia & Analgesia: “Paul Janssen was unique in building the research of his company around his people, not the other way around. He gave all his coworkers the greatest possible latitude in their area of expertise, while he determined the general direction it would go. He acted firmly but also with great respect for the qualities of his associates. He had the talent of being able to stimulate and encourage them by continually nurturing their hopes.”

Janssen drove himself to turn up new ideas no less relentlessly than he did his staff. Lewi and Smith recount that Janssen was constantly scanning pharmaceutical and chemistry journals, taking notes on what caught his attention and compiling these thoughts into an in-house newsletter. He also relentlessly followed up on his questions with colleagues around he world. “There was no place for scientists to hide and avoid exposure to the question ‘What’s new?’” Lewi and Smith recalled.

Throughout his lifetime, Janssen oversaw and directed the expansion of Janssen Pharmaceutica’s product line and activities. New initiatives of special relevance to health in developing nations pursued treatments relevant to parasitology, mycology, and neurology. Departments for veterinary medicine and plant protection were added in 1964 and 1972 respectively. These efforts yielded a host of drugs for combating parasitic worms, molds, diarrhea, nausea, and psychoses. A global network of subsidiaries grew up around the world, including a history-making facility in the Shaanxi province of China in 1985, which was the first Western pharmaceutical factory to be established there.

In 1995, Janssen and Lewi co-founded the Center for Molecular Design, where they investigated and developed anti-HIV compounds including the diarylpyramidines. One of Janssen’s most cherished hopes was to develop a successful treatment for multi-drug resistant tuberculosis, a highly elusive goal. That work came to fruition in 2012 when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved bedaquiline, a compound developed by Janssen Pharmaceutica researchers, as part of a compound therapy for adult TB patients. Approval in the European Union followed two years later.

Paul Janssen did not live to see that success; he died unexpectedly at age 77 on November 11, 2003, during a visit to Rome. He was survived by his wife, Dora, their five children, and 13 grandchildren—but also by an unmatched record of achievement in pharmaceutical science. During his lifetime, Janssen’s accomplishments earned him dozens of scientific and medical prizes and honorary degrees. In 1990 King Baudouin of Belgium elevated him to the peerage by conferring a barony on him.

The long list of drug treatments to his credit and the pharmaceutical research company that bears his name are both monuments to his singular genius. Yet the tribute that might best honor the innovative spirit of the man is the Dr. Paul Janssen Award for Biomedical Research, which Johnson & Johnson founded in his memory in 2005 to “promote, recognize and reward creativity in biomedical research.”